An ounce of prevention may be worth a pound of cure, but, as I used to tell my medical students, physicians get paid by the pound. We lavish money on those who cure our disease, but no one has ever sent out an invoice for a disease that they prevented. We don’t complain when the air isn’t dirty. We don’t call the Mayor when the water tastes fine. We don’t find a lawyer because we didn’t get cancer after an EPA regulation stopped exposure to carcinogens. And if public health workers had managed to confine the pandemic to Southeast Asia, it would have only enhanced our adolescent sense of invulnerability.

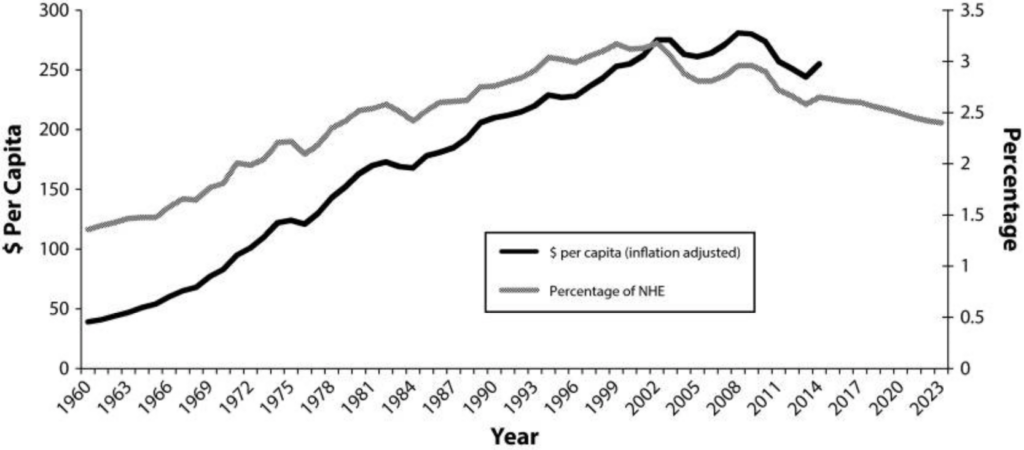

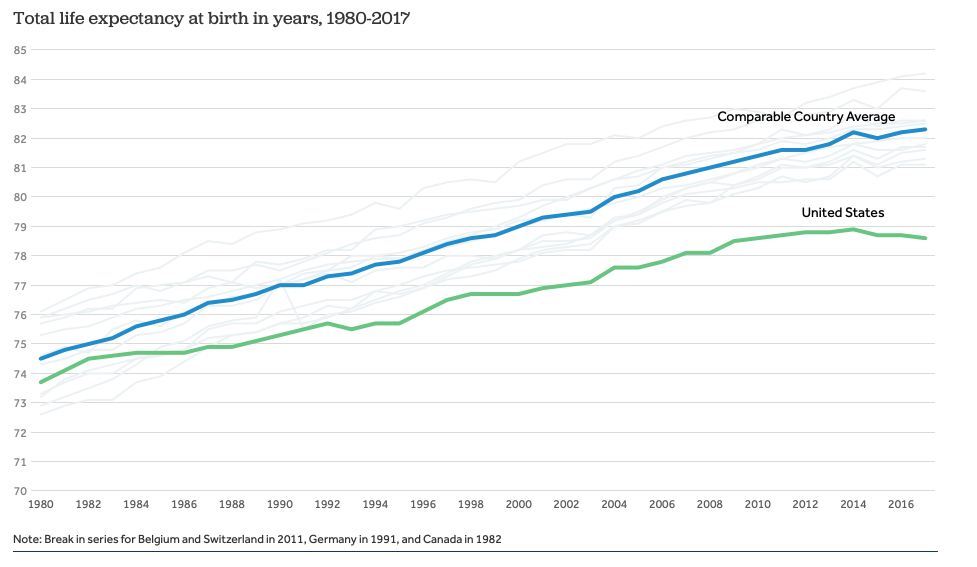

At a superficial level, we have failed in terms of financial support. For every one of the $3.6 trillion we spend on health care each year, we spend about 2.5 cents on disease prevention, a number that has been declining since 2002. In other words, for every ounce of prevention we buy, we are paying for two and a half pounds of treatment. That failure to fund prevention, coupled with a lack of universal health care, helps explain the fact that life expectancy in the US is almost 4 years lower than that of comparable countries, despite that fact that we spend at least 50% more per capita on health care than the next highest spender.

A deeper dive reveals something more disturbing. At its core, disease prevention relies on faith in science, particularly science that predicts what would happen if we didn’t act. Money spent to reduce airborne particulates, to keep carcinogens out of drinking water, or to study emerging pathogens in remote countries has no visible pay off, because understanding the savings in lives and money requires belief in science. Mandatory vaccination might seem like government overreach to anyone who has not seen a deadly disease outbreak in action. In a simplistic, business-minded perspective, these expenditures make no sense, providing no clear return on the balance sheet. Only the science tells us what would happen if we did nothing, a scenario that epidemiologists refer to as the “counterfactual”.

Yes, regulations and interventions to protect public health cost money and create inconvenience. They only exist because of the “counterfactual” reality described by the scientists. In a world of short-term thinking, they are tempting to ignore, particularly when those benefitting from public health expenditures are not necessarily those bearing the cost. And those bearing the costs often have money. Lots of it. Couple that reality with the uncertainties inherent in predictive science and you have the basis for the war on science that has risen to blitzkrieg proportions under the current administration.

The assault on public health science is being perpetrated with Machiavellian ruthlessness, most of it out of public view, timed and orchestrated to allow for minimum oversight. Throughout government, serious scientists have been excluded from review panels and those within the agencies have been terrorized and marginalized. The Administration has sought to dramatically cut the EPA budget in every funding cycle since taking office. A senior scientist there once described it to me as living in a house infested with termites. It only looks like it is still standing. The story repeats itself in every federal agency charged with protecting public health. Even as the pandemic was unfolding on March 10, the Administration was pursuing a plan to cut the CDC budget by 15%.

The latch on the barn door was broken. The Administration not only failed to get to the hardware store to fix it, but they actively sought to remove the latches from all the barn doors. It’s now far too late to fix the latch. Even a whole new door won’t help, because, in this case, the horses not only left, they kicked over a lantern and burned the barn to the ground.

Now, an Administration that has sought to cut the CDC’s $6 billion budget in every funding cycle has signed off on a $2 trillion plan to rebuild the barn. As we stand in the smoldering ashes, let us remember that a disdain for science set it on fire.