A recent working paper from the Center for Health Economics and Policy Studies (CHEPS) concluding that the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally led to over 250k new cases of COVID-19 in the United States has provoked a storm of condemnation. But not of the rally. The messengers are under fire. The editors of the Wall Street Journal have called it a “Statistical Misfire”. South Dakota Governor, Kristi Noem, has dismissed it as “back-of-the-napkin” math. Even serious epidemiologists have jumped into the fray arguing that the results just don’t “seem plausible” or don’t “pass the sniff test”. The epidemiologists raise concerns about the methods used by these investigators. Their arguments have merit, but don’t justify ignoring the study findings. In fact, the critics may have missed something critical in dismissing the study estimate as too high. It may be too low.

sturgis = 70,000 Weddings

No one doubts that the Sturgis rally, which brought as many as 460,000 aging motorcyclists to an otherwise unremarkable town in western South Dakota for a ten-day long, booze-soaked party, caused new cases of COVID-19. But how could one event cause over 250,000 cases? To understand this, consider a recent wedding in Maine.

To ensure they were safe, the 62 guests underwent temperature checks as they joined the reception. Thus reassured, few wore masks as they ate and drank and danced to celebrate the marriage. But one guest brought an unfortunate gift to the wedding. SARS-CoV-2. Less then a month later, that single event, lasting just a few hours, had resulted in 123 cases of COVID-19.

Think of Sturgis as 7,000 weddings. Not all of them were superspreader events, but some of them almost certainly were. Now imagine that the guests from each of those weddings all went off to new and different weddings the next day. Repeat this for ten days. In the face of 70,000 day-long weddings, a count of 250,000 cases of COVID-19 starts to seem not just plausible, but inevitable.

Plausibility: Top Down

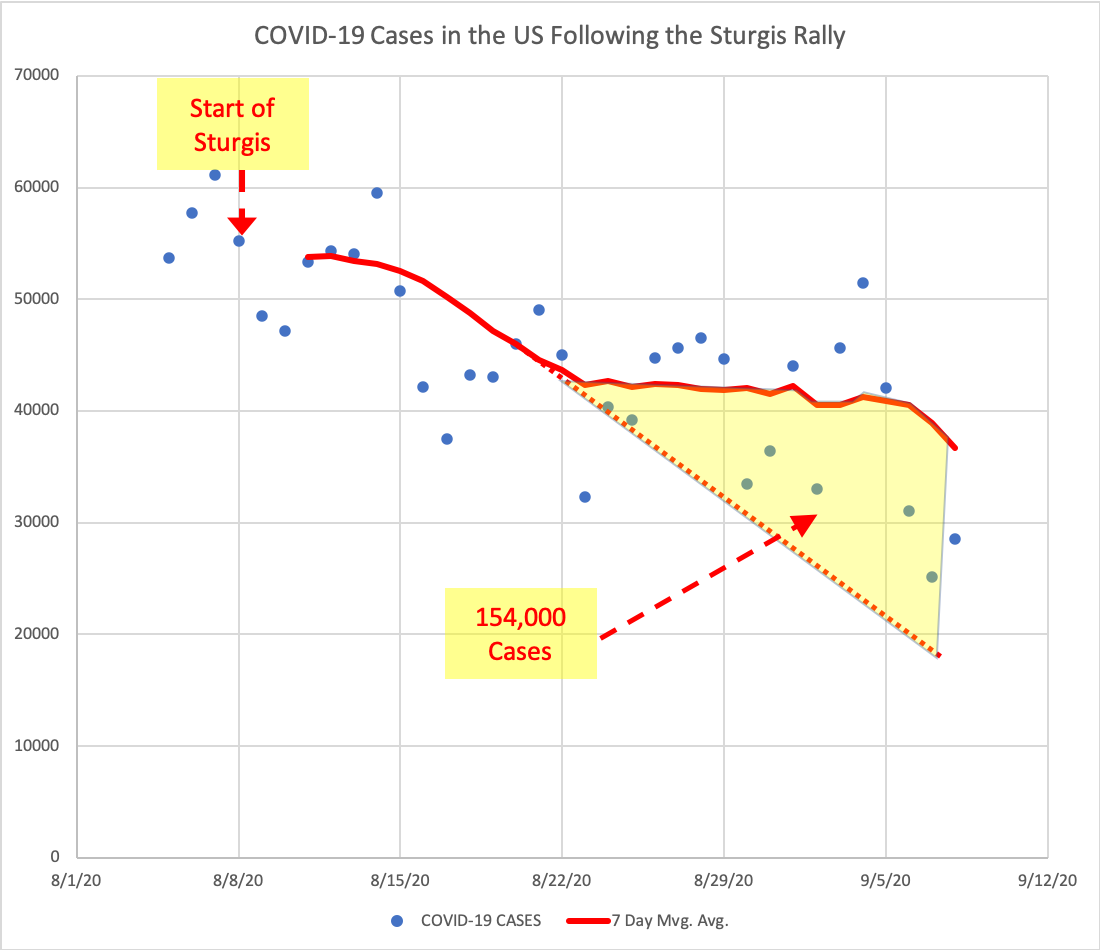

Sturgis Motorcycle rally representing 154,000 cases.

We can look more specifically at plausibility by looking at the numbers. There are two ways to do this: top down or bottom up. The top down approach is to simply look at the number of cases in the US and see where those cases might be hiding. When we do, we see that something quite striking happened about two weeks after Sturgis. Figure 1 shows that the daily count of new COVID-19 cases at the time of the Sturgis rally was trending steadily downwards. Two weeks after the start of the Sturgis rally, the decline abruptly stopped and did not begin to drop again until two weeks later. We can’t be certain this change is related to Sturgis, but the timing is about right.

Imagine the rate of decline we were seeing during Sturgis had continued after the event. That would give us the dotted line. How does the the number of cases represented by that line differ from what actually occurred? 154,000 cases. The timing of this bulge in the epidemic curve is consistent with a causal role for Sturgis, but doesn’t prove it. Something else happening in the same time window could be responsible. Maybe this is just the result of too many frat parties. But something thwarted control measures and resulted in many tens of thousands of cases of COVID-19 that might have been avoidable. That cause could be Sturgis.

Plausibility: Bottom up

Another way to look at plausibility is to model the spread of the virus. At the time of the Sturgis rally, about 50,000 Americans per day were testing positive for COVID-19. That translates to an average rate of 15 cases/ 100,000 people per day. That’s 68 cases/day in 460,000 attendees. People infected first become contagious about three days after exposure to SARS-CoV-2. In two more days, they develop symptoms. These numbers vary from person to person, but for our purposes, it works to simplify. At the start of Sturgis, we can expect that our crowd will have 204 people who are infected but not contagious (68 per day times 3 days) and 136 who are contagious but not symptomatic (68 per day times 2 days).

In these immense crowds, with no masks, it is not unreasonable to think that each person infects three people in the course of a day. After all, a single person infected 51 in two hours at a choir rehearsal. So, three in a full day of partying is, at least, plausible. I have also assumed that, once someone has been infected for five days, they have symptoms and remove themselves from the crowd. This is conservative since some will have mild symptoms and stay with the party that they have travelled hundreds or thousands of miles to reach.

So, 204 people show up infected, but without obvious symptoms. 136 are already spreading SARS-COV-2, infecting 408 (3×136) on the first day. In the others, the disease will become contagious over the coming days. As people become newly infected, they join the cue to start spreading the disease. [This is all on a simple spreadsheet I am happy to share with anyone interested who wants to play with the numbers.] If we play this game of exponential growth for ten days, we would have 28,000 COVID-19 infections by the end of the rally, almost all of whom have yet to show symptoms. Now we send them home.

When they get home, the party has stopped, but the spread continues. Even if each infected person infects an average of only 0.8 people each day, we would see huge numbers of cases. (Note that means each case infects 1.6 people. The average is closer to 1.0 now, but people who will to party for 10 days without masks will be more likely than average to spread the virus at home.) The total two weeks after Sturgis? 212,000 cases of COVID-19. Again, one can argue about specific numbers, but the results clearly demonstrate plausibility. 250,000 might be high, but it is clearly not unthinkable.

The STURGIS COVID-19 Study

Of course, the only way to fully understand the impact of the Sturgis rally, would have been to track each of the attendees and see who developed COVID-19. Absent a surveillance state, that’s not happening. And even if it did, we couldn’t be sure how many of those people would have gotten sick without going to Sturgis. We would need to have controls, people who are exactly like the people at the rally, except they didn’t go.

The authors of the CHEPS study didn’t have controls. In fact, they didn’t even have people. They had counties. They could look at rates in counties and compare them. But there was no simple way to know how many people from a given county went to the rally. However, by using anonymized cell phone data, they were able to estimate the number of attendees returning to each county and estimate the impact those returnees had on local incidence of COVID-19.

All of these designs are flawed. All can be critiqued. That is inherent to epidemiology. A friend once defined epidemiologists to me as “people who criticize the work of other people who also call themselves epidemiologists”. Nonetheless, using three completely different approaches, all of these studies suggest there is a real possibility that this single event, this mother of all superspreaders, could have caused more than 100,000 cases of COVID-19. But there is one flaw that could make all of these studies underestimates.

Exponential Growth is a Bitch

The mistake that all of these approaches have in common is that they assume the story ends neatly, two weeks after the event. But the disease is still there. And it’s spreading. If we assume Rt has dropped to 0.9, the point estimate for the lowest value of Rt we have seen in the US, this model estimates 360,000 cases of COVID-19 two weeks later (4 weeks after the Sturgis rally started). Two weeks after that, over half a million.

What if R isn’t below 1.0? An R of 1.2, sustained for six weeks after the return of the Sturgis rally would give 1.3 million cases. This is not a likely event, but these numbers give a sense of how easily an outbreak gets out of hand and how essential a sustained effort is to controlling it.

A recent study of an early outbreak in Boston that involved 175 executives from Biogen gives a sense of how much impact even a single case can have. One infected executive led to 99 infections within a few weeks. Then, five months later, investigators concluded that the unique genetic signature of virus found in that index case has since been found in 20,000 cases. All from that one source. Exponential growth is a bitch.

The bottom line is that Sturgis, an event held against both the advice of the experts and the wishes of the local community, was an open invitation to disaster. It is certain that it caused disease and death, quite possibly on an epic scale. But its lessons seem lost on leaders such as Kristi Noem who is hell bent on dismissing it. At the masks-off South Dakota State Fair over last weekend, she carried the flag on horseback at the opening rodeo.

Your bias leads you astray. You mentioned in passing “frat boys” having parties, and possibly spreading the coronavirus that way, but don’t follow the trail. You grossly underestimate the probable count of students catching the Coronavirus as they go back to college.

For example, the University of Alabama and University of Georgia each had over 1,000 students test positive for the coronavirus in August. Hundreds of other large universities opened around the country in the same timeframe as the Sturgis event. You have no idea of how many thousands of cases occurred as a result. (BTW, the effects on young people are much less severe on the whole than on the elderly.)

Also, you make a basic mistake when you confuse the coronavirus and COVID-19. The former is the virus, which people test for, and the latter is the illness the results from the virus. Testing positive for the Corona virus does not mean that you have COVID-19. In fact, most people who get the virus don’t get sick from it or show symptoms. A very small percent are hospitalized, which is one reason the 12 billion dollar cost estimate is ridiculous.

Please read the Slate article that debunks the study.

Thanks for your comment. I’m not sure what bias you are referring to. Yes, I find the actions of the current administration with respect to COVID-19 abhorrent, but my disdain does not drive my science. On the contrary, my understanding of the science drives my disdain.

With regard to your specific comments, some of the excess cases in August are related to college openings as I noted. There are 443 colleges planning to open primarily in person this fall, but most did not open in August (https://collegecrisis.org). That doesn’t seem consistent with the relatively abrupt shift in the trajectory in daily case counts in late August. My argument is focused on plausibility and it is certainly plausible that the bulk of these additional cases are related to Sturgis.

With regard to the case definition for COVID-19, you are incorrect. Here is the confirmatory case definition from CDC: Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 ribonucleic acid (SARS-CoV-2 RNA) in a clinical or autopsy specimen using a molecular amplification test.

I read the Slate article. She is wrong and makes the mistaken assumptions that I address.