CHAPTER SIX

The Note

The flood of memories begins as I approach the hospital, but, when I go inside, the tsunami hits. The trees in the lobby, the painting over the reception desk, the swirling mobile, even the squeak of my shoes on the floor and the smell (that weird hospital smell like bandaids and rubbing alcohol) bring back the endless hours of waiting, the whispering adults who never gave me a straight answer, the books and bad TV that was supposed to keep me busy while I couldn’t see Mom when that was the only thing I wanted.

Most of all, I remember feeling helpless. Like I could have done something. And I remind myself of the promise I have made to myself over and over that it would never happen again.

I remember that promise as I march across the lobby to the information desk. Strong for Dad I tell myself. “Hi, I need to find the room for Dr. Charles Boston.”

The receptionist looks up at me. “I’m sorry, what was that name?” Her southern voice hangs on to each word like it doesn’t want to let it go.

“Boston, Charles Boston. B-O-S-T-O-N.”

“And you are?”

“Jack Boston. His son.”

The woman at the desk speaks through a thick layer of make-up and bright red lipstick. Her hair is this too-dark-to-be-real shade of black. “What is your father’s date of birth?”

“September 1, 1965.”

She taps at her keyboard with long fingernails. A look of concern cracks her foundation. “I am terribly sorry, but your father is in isolation in the ICU. You can’t see him.”

Those three letters almost knock me over. The three letters that took Mom, locked her away from me. The place she went to die. But I had a promise to myself. “I have to see him. I’m his son.”

“I’m terribly sorry, but this is an order from the CDC, the federal government. Only medical personnel are allowed access to patients in isolation.”

“You mean that I can’t see my own father.”

“I really am sorry, hon, but those are the rules.”

“I was just with him this morning. Why can’t I see him now?”

“Patients in isolation can not receive visitors. Those are the rules. I wish I could change ’em for you, but I can’t.”

I stare at her.

I watch her face turn into an apology. “Would you like to talk to his doctor? Or maybe a social worker? They could at least tell you what’s happening with your father.”

I start to say yes and then stop. I remember the policeman with the quarantine sign. If I’m not careful, I will wind up locked in my house with an armed guard before I have a chance to talk to Dad. I can’t afford to let anyone else know I am at the hospital. “No thanks, ma’am. I’ll just head home.”

“You sure? It’s no problem.”

“No, that’s fine. Thanks.”

I glance around. For a moment, I consider just walking up to the ICU and going to see Dad. Typical hospital security is a pretty casual deal.

I glance at the hallway that leads to the elevators. Two buff guards in blue fatigues and fierce buzz cuts look back at me. Both are sporting mean looking MP5’s.

This is not typical security.

I walk out of the hospital in a daze and slump down against a column next to the bike rack.

The ICU. I can’t believe it. ICU. Those three letters were at the center of the worst two days of my life. Hospital policy. No visitors under 13 in the ICU.

So I had spent two days trapped in lobbies and waiting rooms or stuck at home, monitored by a string of caregivers, while Mom died in the ICU.

In the end, Dad had smuggled me in. I had glimpsed my mother, wrapped in bandages and surrounded by tubes and machines, unable to speak or respond to me. Six hours later, I was in the waiting room when she died.

Now, the ICU has Dad.

But this is different.

Dad is not in a coma. He just needs some oxygen. He has gone to the ICU to recover.

He is probably feeling better already. Maybe it’s just a precaution because of the outbreak.

Then I realize I could call him. I could talk to him. Maybe that will be enough. Then I can go home.

I pull out my phone and dial the main number for the hospital.

I punch my way through the maze of automatic operators and, after listening over and over to a cheery recording telling me someone will be with me shortly, a human voice startles me.

“Washington General. May I help you?”

I raise my voice an octave. “Hi. This is Dr. Margolis. Could you connect me with the ICU, please?”

“One moment, Dr. Margolis.”

That was almost too easy. A woman’s voice. “ICU.”

“Hi, this is Jack Boston, my father, Dr. Charles Boston, is a patient there. May I speak with him?”

“His date of birth?”

“9/1/65”

“Just a moment please.”

After a few minutes, another woman’s voice came on. “Hello, this is Dr. Jackson, is this Charles Boston’s son?”

Crap. I push the END CALL button.

I let the phone drop, close my eyes, and cup my hands to my face. And, for the first time since Mom died, I cry.

I struggle to stop. Somebody will save Dad. Dozens of epidemiologists, physicians, and microbiologists from the University and the Department of Public Health and the CDC are already working on this. It might take some time, but eventually they will figure it out. Eventually Dad will come home.

“… nobody’s getting well … until they understand this.” Dad’s words blow through my denial. Going home and letting them lock me up is the worst mistake I can possibly make.

The only way to save Dad is to find a way into his head. But I can’t talk to him.

But I have to do something. Everyone else has this wrong. That’s what Dad said. And now I have to unravel his theory. I have to assemble the proof that Dad was putting together last night.

But how? I have no idea what the theory was, much less how to prove it.

The map. Dad wanted people to see the map. Something in that map will explain his theory. If I can find the map on Dad’s computer, I can begin to unravel the mystery. I don’t know what I am going to see, but I tell myself that it holds the answer.

All I need to do is go back to the house.

And get out again.

I jump on my bike and ride.

***

Five minutes later, I stash my bike in a clump of trees two blocks from my house. Not sure who might be watching I approach with caution.

There is no one in sight, but I turn down a side street and duck into the alley that runs behind my house just to be safe. The coast is still clear.

I crouch low, staying next to the fences and garages. If anyone glances up at the alley, I do not want to be seen.

Moments later, I reach the bushes behind my house. Looking through, I see a clear path to the basement window, the one with the lock that doesn’t work. A quick scan. No one is watching. I sprint across the grass and drop into the well of the defective window.

And then, I’m in.

The basement smells like laundry. The floorboards above me creak. I freeze. Someone is in the living room. Someone heavier than Abe or Sam. The nurse.

If the nurse stays in the living room, I can climb the basement stairs to the kitchen and get to the second floor without being seen.

For a minute I wait and listen. The creaking stays in the living room. At the bottom of the stairs, I pause and listen to the kitchen floor. Nothing. I climb, keeping my feet on the edges of the treads so they don’t squeak under my weight. As I reach the top of the stairs, I hear voices.

I listen. “Some are sad and some are mad and some are very, very bad.” One Fish, Two Fish? I wince. The boys have been reading that to themselves for over a year.

For a moment, I feel guilty that I abandoned my brothers, but I bury that and creep up to the second floor. Working my way past each loose board, I make my way down the hall and up to Dad’s office.

The full heat of the summer afternoon fills the third floor. It feels like a sauna.

To call it a third floor is generous. Dad walled off half of the attic after Mom died to make an office so he could work from home. But it’s still an attic.

I step into the office. The large fan that normally pulls hot air out of the attic is off. I close the door, turn on the fan, and sit at the keyboard to Dad’s computer.

Not sure how much time I have, I enter Dad’s password, 123456. I have reminded Dad more than once that this was the world’s worst password and have been telling him for months that he needs to pick a better one. Right now, I’m glad Dad doesn’t take computer security seriously.

The login screen reappears. “Please, reenter user name and password.” Crap. Maybe I mistyped, I try again. No luck.

I just used the password last weekend. Dad picked a hell of a time to start worrying about hackers.

I go into my own account and start a program to crack the password. But that will take time.

If it works at all.

OK. Plan B. I scan the room. What else do I have to work with?

Dad’s desk overflows with papers, journals, books, notebooks, and pads. I’m sure everything is carefully organized, but only Dad could understand it.

I begin to dig through the piles, not sure what I’m looking for. On one side of the desk are stacks of journals that look like they’ve been there forever. Forget them. I wouldn’t know what to do with them anyway. There’s a bunch of articles, but they have Ebola in the title. I read The Hot Zone. Ebola makes you bleed out of your eyeballs or something like that. Strike two. A messy stack of printed pages is marked up in red, but it just looks like something he’s editing and he wouldn’t be editing anything about the outbreak.

A stack of bills, some unopened mail. Nothing promising on the desk, but then I see the black notebooks. I pull one out. It’s filled with lists, notes, formulas, and the occasional name and phone number. It all looks random, so I grab another, but it looks like another mix of irrelevant stuff. So I pull out the one at the end of the shelf. This one is only half full and the last ten pages are filled with a list of names, numbers, and addresses with what appear to be dates and times. The dates are recent. But there’s nothing else. No clue to Dad’s thoughts, no analysis, just precise, handwritten records of person after person. But I know in a moment what I’ve got.

This must be the raw data on the outbreak, the names and addresses of the victims. But, without Dad’s analysis, I don’t know what to do with it.

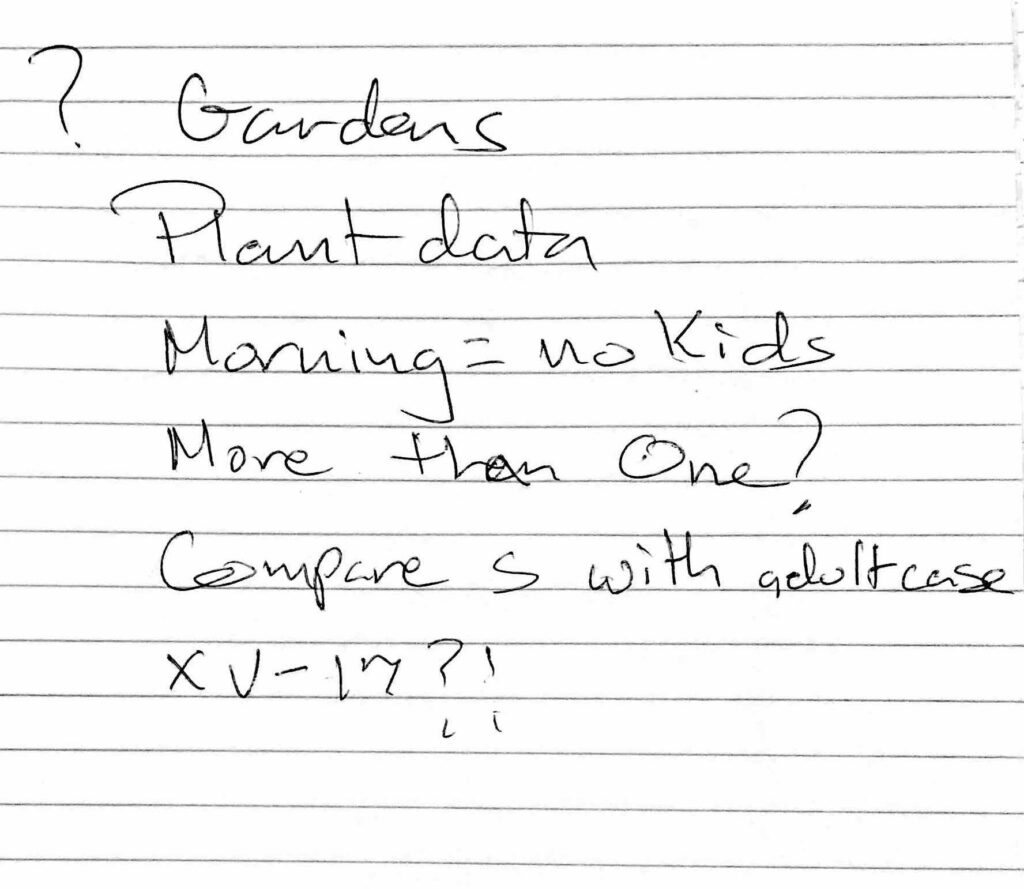

Then, I see the pad sticking out from under the edited manuscript. On it are six lines in Dad’s handwriting.

This is it. It’s what he was writing last night. While he was on the phone. I saw him write it. It is the secret of the outbreak. And, to saving my father.

But I have no idea what it means.

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Twentieth Floor

Kurt hates to lose. But he especially hates to lose to a loser like Jack Boston. As his father used to say, “Losing just means you haven’t considered all of your options.” He remembers exactly the first time he heard it.

It was during the finals of the New York State U14 soccer championship. Kurt’s team had outshot their opponent 12 to 2, but we were down 1-0 at halftime when his father, walked out like he owned the field and grabbed him and held him so their faces were inches apart. “Would you mind telling me what the hell is going on out there?”

When his father got that look in his eyes, Kurt knew to be careful about what he said. “That keeper is too good.”

“Bull. Nobody’s ‘too good’.”

“I’m doing everything I can.”

“Do you want to lose? It sounds to me like you want to lose. I did not cancel a meeting today to watch you lose.” This was the first game of his that his father had attended in two years.

“Why would I want to lose? I always play to win.”

“No you don’t,” Dad growled.

“Of course, I do.”

“If you are playing to win, why the hell are you losing?!” Dad hissed through clenched teeth.

“I told you. That keeper is amazing. I am doing everything I can.”

“If you think that kid is so damned amazing, why don’t you just go take a shower now? If you think losing is an option, you will lose. If you are losing, you are not doing everything you can.” Victor Eigen was turning the blend of brilliance and ferocity that had made him a billionaire on his son. He pointed his finger at Kurt’s face. “There is always a way to win.” On the word, “always”, he drew back his hand and hit Kurt in the center of the chest with the tip of finger with so much force that it knocked him backward. “You are just not letting yourself do it. Losing just means you failed to consider all the options.” With each “you”, Victor Eigen struck his son on the chest again with a pointed finger. With each hit, Kurt stepped back and his father stepped forward. “If you consider all of your options, and I mean all of your options, you will win.” His father paused as Kurt tried to make sense of what he was saying. “And I expect you to win.” Without another word, he spun on his heel and strode off the field.

Kurt had no clue what he was expected to do, but he knew he had to figure it out. Ten minutes into the second half, he did. He was racing to get a ball in front of the goal when their keeper dove on it. He first started to pull up short. That’s when he finally understood the precise meaning of his father’s words.

Kurt accelerated, planted his left foot, cocked his right and swung at the ball with everything he had. His foot arrived, full force, just as the keeper wrapped his hands around the ball. He could hear the crack of broken bones as my foot crushed the keeper’s left hand. He sailed over the keeper and tumbled to the ground holding his foot in pain. The foot was bruised, but not broken. The keeper, meanwhile, was writhing on the ground and screaming in agony.

Kurt looked up to see the ref standing over him, holding a red card in the air. As he hobbled to the sidelines amid jeers from the families of the opposing team, he looked at the stands just in time to see his father smile and nod his head.

Kurt spent the rest of the game watching from the sidelines as his team scored three goals against a far less agile second-string keeper. He felt a twinge of guilt as he watched the EMT’s load the keeper into an ambulance. But he got over it. After all, he had won the game and the state championship without even being on the field.

***

In bare feet, jeans and a white tee shirt, Kurt leans back in his desk chair and sips a latte. He stares out through the huge glass wall of the twentieth floor apartment. Students at the Academy who don’t live in Seattle are required to live in the dorms, a couple of old apartment buildings a few blocks from Campus. When Kurt started at the Academy, his father, bought a glass, 20-story high-rise. He then declared the building’s penthouse apartment as their legal residence. It was an open secret that Kurt lived there alone (not counting the cook, the chauffeur, and the housekeeper).

To the north, a seaplane is landing amidst the boats that crowd Lake Union. To the west, the sun is glinting off the Olympic Mountains and the steady stream of Ferries, cargo ships and tankers making their way across Puget Sound.

Kurt looks back at the screen of his computer and rereads the email. There is more than one way to win. It’s time to break the keeper’s hand.

Kurt types the address, seattle@ FBI. gov, and presses send.

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Puzzle

I’ve never been much for biology. Way too squishy. And all the names and memorization. Give me predictable and logical. Physics, math, computers, robotics. I suppose, living with Dad and all, I have picked up a lot about medicine, but not enough to solve this puzzle.

So, I punch Athena’s button and she answers on the second ring. “Hey, Jack. Where have you been? Did you hear they postponed Robowars? They say there have been more cases, another outbreak.” A long pause. “Jack? Is something wrong?”

I have forgotten how much I would need to explain to Athena. “It’s my dad. He …” For a moment, the words won’t come.

“What is it Jack? What’s wrong.”

“The …” Trying to describe it makes it real.

“Is he OK? What happened?”

I force the words out. “He’s got it.”

Athena gasps. “You mean … you mean the virus?”

“Yeah.”

“Oh my God. Jack, I’m… I’m so sorry. How bad is he?”

“He’s in the ICU.”

“How’s he doing? Oh, yeah. Stupid question. I mean … Well is he going to be OK?”

“They …” The question forces me to imagine my father in the ICU, a leap of thought I have been avoiding. “They won’t even let me see him.”

“How can I help?”

I feel the weight that’s been on my chest all-day lift. Slightly. At least I feel I can breathe.

I tell her everything, from the cough in the night to my search for clues and the note.

“So, send the note to the CDC.”

“I can’t. My dad said the CDC was headed in the wrong direction. He spent most of last night trying to convince his public health buddies he was right. They weren’t buying it.”

“It’s the C D C,” Athena separated the letters, leaning on each one to remind me how foolish I was. “The best epidemiologists in the world. This is what they do. Let them do their work. They’ll figure it out. If you absolutely have to do something with the note, send it to one of your dad’s epidemiology friends.”

“They told him they don’t buy his idea.”

“So what are you going to do, solve this thing yourself?”

She won’t like my answer.

“No, Jack. Please tell me you are not thinking you’re going to crack this thing on your own.”

Definitely won’t.

“You are, aren’t you? You’re thinking -“

“Athena, I need your help. Dad said, ‘They’ve got it wrong and nobody’s getting out of the hospital until they get it right.’ He said he might be able to help them with a vaccine, maybe even a cure.”

Silence.

This is my opening. “What would it take for anybody to save him?”

Long pause before Athena speaks. “We have three or four days to stop the infection. Somebody will need to figure out an …”

“Three or four days? What happens in three or four days?”

“That’s how long it takes the encephalitis to develop.”

“Encephalitis?”

“Right. An infection of the brain.”

“Brain infection? What do you mean, brain infection? I thought this was just some kind of pneumonia.”

” You don’t know? You haven’t been following the news?”

“Not exactly.”

“Well. In the past 24 hours, seven people who were recovering from lung infections developed encephalitis.”

I drop down in Dad’s chair. The only thing I know about encephalitis is that it kills people. Then it hits me. “That’s the twist.”

“What?”

“The twist. Dad said there was twist coming. He said people would die. I don’t know how, but my father knew something like this would happen.”

“What are his chances of surviving encephalitis?” I think I know the answer.

Silence.

For a moment, I just stare out the window. Blue sky and the sun in the maple tree.

“My dad said something about a cure.”

“I … It’s a virus. Not many drugs … Maybe a vaccine, but ….”

“The note. Maybe there’s something in the note.” I snap a picture, shoot it to her, and wait.

Compare S with sample from adult victim

Athena finally speaks. “Not exactly transparent. Plants? Gardens? Sounds like he’s talking about contaminated fruits or vegetables. But that wouldn’t make sense. I mean, a foodborne outbreak doesn’t usually cause a lung infection. I think the CDC even checked on food as a source. Nothing.”

I keep pressing. “What about the next part, the bit about no kids?”

“I have no idea why he’s talking about morning. Almost all of the people in the hospital are adults or teenagers. Kind of weird. Kids are usually the first to get sick. The reason that happened might help explain how this thing is spreading. But morning? I don’t know.”

I move down the list. Something in the note has to click with Athena. “How about, ‘More than one?'”

” It could mean anything. More than one outbreak. More than one source. More than one test. I don’t know.”

“XV-17?”

“Nothing.”

“Damn. Come on. Last clue.”

Athena reads it aloud. “Compare S with sample from adult victim.” She pauses. “That sounds like he wants to look for the virus in two different samples, one would be from an adult with the disease. The other, I don’t know. Maybe from a kid with the disease.

“I thought there were no kids with the disease.”

“There are three kids who got sick. Maybe he thinks there is something significant about those kids. Exceptions often provide critical clues.”

“What kind of sample is he talking about?”

“Probably a sputum sample. It’s a fluid sample from deep in the lungs. It would be loaded with the virus.”

“Do you know how to analyze a sputum sample?”

“Yeah. At least some of the tests. But-“

“How long does it take to do the test?”

“Not long, a few hours, but Jack-“

A door slams. Sounds like an outside door. Someone new is in the house.

“Gotta go,” I whisper. “Talk soon.” I flick off the phone and got to the window.

The twins are playing in the back yard. The nurse is close on their heels. The door was just the sound of them leaving the house to play.

I slump back into the chair and close my eyes as a plan takes shape. I watch a couple of videos on my phone until I think I know what I need, then head downstairs. In Dad’s bedroom, I find his hospital ID badge on the top of the dresser and a long white lab coat in his closet. Moving to my bedroom, I grab my backpack and shove the coat and badge inside.

I spot an energy bar wrapper in the wastebasket with a bite left inside. I grab it and stuff the remnants into my mouth. Before it hits me that I’m so hungry I’m eating out of the garbage.

I decide to fuel up before everyone gets back inside.

In the kitchen, I find a half-eaten bowl of cereal, soggy and covered with swollen strawberries. I open the fridge and find a bag of cherries, which I toss into my backpack. I grab the milk and, as I pull it out, I see it.

In the back corner of the fridge is a small plastic bag. In the bag is a plastic vial with writing on it. I pull it out. Through the bag, I can read the label. Sam 6/18 02:10.

6/18. The night before last. Sam was sick. The “S” in Dad’s note is Sam.

Whatever the reason, a small piece of the puzzle had just fallen into place.

Click. Bang.

I know the sound. The front door.

CHAPTER NINE

ICU

A hurricane of noise hits the house as the boys burst through the front door. A voice chases them in. “I’m going to start counting!” says the nurse in a loud, kindergarten teacher voice.

I jam the bag with the sample vial into my backpack. The boys thunder down the hall. I hear squeals head up the stairs to the second floor.

“Ten,” the nurse begins to count. I ease the fridge closed. “Nine.” I throw the pack onto my shoulder. “Eight.” I open the door to the basement. “Seven.” A gasp behind me. I spin to see Sam, staring at me with wide eyes. Immediately I raise a finger to my lips.

“Six.”

“No one can know I’m here,” I whisper.

“Five.”

“I didn’t tell her.” His eyes tell me silence has been hard.

“Four.”

I smile at him. “Good work. I’m trying to help Dad.”

“Three.”

“You’ve got to stay quiet.”

“Two.”

Sam looks puzzled but determined. “I won’t tell. Go help Dad,” he says in the loud half whisper of a five-year-old trying to be quiet.

“One.”

I give Sam a quick hug. “Run up and hide.”

The nurse bellows through the house. “READY OR NOT, HERE I COME!”

I sprint down the basement steps. The sound of Sam, pounding up the back stairs to hide on the second floor covers my escape.

***

Twenty minutes later, I’m on the Burke Gilman trail, just across a busy street from the hospital. I ditch my bike in the bushes and slip on the white coat. In the palace of medical care, a white coat is the master key. The first door I open belongs to a small brick office building, just across a busy street from the hospital. Round light fixtures covered with thick layers of brown paint light the industrial green walls of corridor. Halfway down it, I find an unmarked steel door. I duck inside to find a stairway to the basement. And the steam tunnel.

Inside the tunnel the hot air, thick with a mix of grease and dust, reminded me of the hundreds of trips I took through the tunnel with my father as a kid. I always imagined that we were the only ones who knew about it, that it was our secret passageway and not just a way to avoid crossing through traffic in cold Seattle rain. I still remember dad walking down the hallway with a long brisk stride as I strained to keep up, chasing the billowing tails of his coat.

I’m still not big enough to fill that coat. The heavy cotton droops over my shoulders like moss in the rainforest. Even after I roll up the sleeves, the arms almost reach my fingers.

The picture on Dad’s ID badge is an equally poor fit. Dad looks like his Swedish mother. I got Mom’s swarthy Italian face. Hopefully, no one will look too closely.

I’m surprised to find the stairs up to the hospital are not guarded. I race up and peer out the door. The coast is clear. I’m in.

Getting into the ICU will not be so simple.

I wind through the basement corridors. It’s been a long time and I struggle, realizing how much I counted on Dad to know the way.

Then I see the sign, blue with white letters reading, “Daniel Lu, MD, PhD”. Dr. Lu was a classmate of Dad’s at the University of Wisconsin and Dad and I almost always stopped in to visit him on our way through the hospital. I also know there is a storage room just past it.

Inside the storeroom I find row upon row of stainless steel shelves. I step into one of the rows, lean against the shelving and feel my heart pounding.

I catch my breath and begin to search the bins. A surgical cap and mask are an easy find. I pull on the cap and put on the mask in my pocket. I know doctors do not usually wander the halls in surgical masks, but with the outbreak on, I might be able to use it in an emergency.

It takes me another ten minutes of digging to find a specimen kit. I grab it, clutch it to my chest, and rush out down the hall. The kit might even add to my disguise by making me purposeful. As I step onto the elevator, I feel a surge of confidence. Like this might be easy.

That feeling won’t last.

I emerge into the bustle of the seventh floor. As I begin to walk down the hall, I feel like I’m in a spotlight.

Ahead, three policemen are clustered on one side of the hall. The one with the clipboard seems to be doing the talking. All I see is the Glock 22’s on their belts. I pull on the mask and try to make myself invisible, hoping they are preoccupied.

The giant white coat feels more like a sequined jump suit than a disguise. I fold my arms across my chest, hoping to disguise the sloppy fit and stop breathing as I pass.

But they must be preoccupied. Despite the spotlight and the sequined jump suit, none of them notices my tap dance. So, I just keep walking.

Then I see the eagle. My breath catches. For everyone else walking by it’s just a Salish carving of a bald eagle. But when see it hanging on the wall, I see Dad’s face, stained with tears. “Mom’s gone,” he told me. I looked away, stared at the Eagle. I couldn’t see him like that. His whole face was tight, like he was in pain.

I keep walking. I turn and see a large white sign on a post in the middle of the hall. “AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY” Beyond it stand the heavy double doors at the entrance to the ICU. This time I feel it in my gut. I hate that sign. That was the sign that said I couldn’t visit my mother before she died. The memories are stark.

But I can’t think that. Not now. What I have to think about is the armed guard sitting by the door.

I stop. The guard is looking down at clipboard, running his finger along the page.

Then, he looks up.

I am completely exposed. Think fast.

The guard smiles, nods, and begins to speak. “Can I help-“

I raise a hand to cut him off and give an apologetic shrug as I pull out my cell phone. “Dr. Boston,” I say. Pretending to listen, I slip back onto the main corridor and around the corner, out of the guard’s field of view.

I lean against the wall, the phone pressed tightly to my ear, trying to remember phrases Dad used on the phone. “Did you check the electrolytes?” I ask the non-existent caller. “Uh-huh…. Right. What do you have him on?”

I might have bought myself some time, but I still have no plan. The corridor bustles with serious looking people. I feel prickles of cold sweat across my back. I have to keep moving forward. “All right, well I’m up at the ICU. I’ll be down in about twenty…”

A woman’s voice, sharp and commanding, claims ownership of the corridor.

“Code White! Clear the hall!”

A medical team in protective gear is rushing a gurney down the hall. The team consists of three people in surgical masks, gloves, caps and disposable isolation suits. One is pushing and one is carrying a clipboard and barking orders. A third is jogging next to the patient’s head and watching the monitors. He is squeezing what looks like a blue plastic football attached to a tube running into the man’s mouth.

The man with the blue football looks super serious. “We’re losin’ him. Pulse ox is 80. They have a vent ready, right.”

As they approach, I can barely make out the patient through the plastic covering that hangs over the gurney. What I can see is that everyone is leaping to the side as the team barrels down the hall.

Even the cops.

This is my chance. As they make the turn towards the ICU, I join ranks, following just two steps behind them. I swing to the side of the gurney away from the guard and keep my head down.

I stare at the patient, hoping I can ride through on a borrowed ID badge and the tails of an oversized white coat.

Then, out of the corner of my eye, I see the guard stand up.

I brace myself. The guard steps forward and stands in front of the door. I can’t believe I got all the way here and I’m getting stopped at the door to the ICU. I keep my head down, avoiding his eyes, trying to remain invisible.

But the guard isn’t stopping us. Instead he pushes the button to open the door for the team. I can barely restrain myself from breathing an audible sigh of relief as I brush past him.

***

The ICU, we dive into a crowd of doctors and nurses in blue surgical scrubs. Behind a huge L-shaped counter, half a dozen others are busy with paperwork or talking on the phone at the nurse’s station. One is watching the bank of monitors that carries images of the heartbeats from every patient in the unit.

The ICU splits into two hallways on either side of the nurses’ station. Some sort of wall covered with sheets of plastic blocks the corridor to the right. Through it, I can see a second plastic wall. The space in between is bathed in an eerie blue light that makes the wall of plastic glow. It looks like a construction zone from Star Wars.

I stare for a moment. Then I see the sign reading, “CONTAINMENT ZONE. FULL RESPIRATORY PRECAUTIONS!” in large, red block letters. The blue glow must come from some sort of ultra-violet lights for disinfection. Beyond the walls lies the virus and its victims.

The Hot Zone.

That is where I will find my father.

***

I need a plan. In the confusion created by the new patient, I am able to peel away from the team with the gurney and walk down the hallway to the left of the nurses’ station. Glass walled cubicles line the corridor. I step to the nearest one, pull a binder from a box that hangs on the door and pretend to read the medical record inside the way I saw Dad do it a hundred times. That is when I first notice the heavy smell of bleach that hangs in the air.

I need to think fast. The commotion will keep the ICU staff distracted for a moment. When that moment ends, I need to be in the Hot Zone.

“We need a respirator. Now!” barks the woman who had been giving orders in the hallway.

An exhausted doctor in scrubs and 2 days worth of stubble walks over and scans the new patient with an experienced eye. He glances over at the white board behind the nurses’ station. A sequence of black numbers runs down the side of the board. In a grid next to the numbers are names in erasable marker. The tired doctor turns to a tall, powerfully built, nurse. “OK, Mark,” he says, “Suit up and get her into 701.”

As the nurse pulls on a disposable jump suit, the ICU doctor talks to the woman who led the team to the ICU. “Why isn’t she on a portable?” he asks.

“The ER ran out about an hour ago. It’s a zoo down there. There’s another one coming up right behind us,” she answers.

A member of the ICU staff comes and pulls on his isolation gear with a speed and ease that suggests he has done this hundreds of times before. Then he and the nurse wheel the patient into the Hot Zone.

As I watch, a plan takes shape.

***

I will have to wait until just the right moment. I look toward the ICU entrance. When I turn back a nurse is walking straight towards me. Invisibility isn’t working for me. A woman in her thirties with short black hair, she stops just a few feet away with an outstretched hand. “Can I borrow that chart for a minute, please?”

Like most of the people working in the ICU, she looks overworked and exhausted. Maybe she’s too tired to notice me.

“Ah, sure,” I respond using my deepest available voice. She takes the chart from me without a comment and opens it to a blank page.

“Sorry.” She is still looking down as she begins to write in the chart. “Dr. Knight just called in an order.”

The nurse seems to have fallen for my disguise. Then, she closes the chart and looks straight into my face.

She locks on and wrinkles her forehead. “Are you with the ICU team?”

I try not to hesitate. “Yeah, … that’s right.”

Her eyes narrow. “Med student?” Her voice is kind but pointed.

“Yep.”

She stares at me. Seconds crawl by until she speaks again. She shakes her head. “I don’t know. Either I’m just getting older or you guys are getting younger.” She hands the chart back to me. “Here you go.” She pauses, looking me up and down. “You know you shouldn’t be wearing that.”

Damn. Is she just toying with me? I try to smile back at her, saying nothing.

“You should know better.” Her voice softens. “Where is your short coat?”

I look down at my long white lab coat. It never occurred to me that there was some importance attached to coat length. I can only shrug his shoulders and adjust my surgical cap. “At the cleaners.”

“Well, you’d better get it back. Put that long coat away until they start calling you doctor.”

A smile crosses her face. She shakes her head and waves a finger at my mask. “You probably don’t need a mask just to read Mr. Osgood’s chart. I suspect the risk of infection from him is low. He fell off a ladder.”

The nurse spins around and marches back toward the nurses’ station. This won’t last.

The doors to the ICU burst open. Another team rushes a gurney draped in plastic toward the nurses’ station.

Time to go.

I skirt the buzz that has formed around the new patient until I reach the entrance to the Hot Zone. Imitating what I have seen, I put on a protective suit, paper booties, a cap, a mask, and gloves. As I get ready, I glance at the white board behind the nurses’ station. Room 712. Boston. I stuff the specimen kit inside my jumps suit and enter the blue glow.

The sections of plastic in the first wall bulge into the decontamination area as if a wind were blowing on them. I can hear the faint whir of fans. It must be some sort of air filtration system. I open the door in the second wall and step into the Hot Zone.

***

I’m in. This is good. Getting the specimen might be tricky, but it should be easy after that.

In 701, a team of doctors and nurses hovers around the new arrival, struggling to stabilize him. I keep walking. In each glass-walled room, I can see the outline of a patient surrounded by a nest of tubes, cables and machinery. They are all fighting for their lives. At the end of the corridor, I find room 712. I check the name on the chart.

Charles Boston.

I put my hand on the door and hesitate. Focus. The door makes a crisp sucking sound as I ease it open. My heart races as I step inside.

As the closing door seals me in, I stop and stare.

I know it’s Dad, but I hardly recognize him. His eyes are closed. His face is grey and stubbled and tired and older than I have ever seen him.

His mouth is half covered with tape. A tube jutting from the tape connects to a hose, which snakes to a machine on his right. The machine emits a slow whoosh, whoosh, whoosh.

An IV tube emerges from a bandage on his left arm and stretches across to a bank of IV pumps, each one whirring at different pace. Above the bed, I can see the beat of his heart marked in jagged orange lines.

“Hi, Dad.” I say, knowing he can’t hear.

I knew Dad was sick. But in that moment, as I watch and listen to the beat of his survival machines, I feel like death is just outside the door.

Read the next section, Chapters 10-12