I’m not sure who designed the New York seroprevalence study. It’s not even clear that it was designed at all, because the only description of it is an audible from Governor Cuomo stating that sampling was done outside supermarkets and shopping areas. That raises a huge red flag for epidemiologists.

The challenge the New York researchers faced is how to describe the prevalence of antibodies in the entire population when they could only test a small fraction of that population. How epidemiologists choose that sample is critical to the validity of the sample. Testing hospital workers would give very different results from families that have stayed home and ordered everything online. What we need is a random sample from the population, but random samples are the kind of thing that keeps epidemiologists awake at night. (Yes, we’re that boring.)

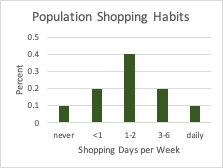

Let’s look at the sample used in the New York study. Consider who is likely to be outside of a supermarket or a shopping area. Maybe shoppers? In fact, the more often you shop, the more likely you are to be outside the market on any given day. To see the implications of this, assume the distribution of shopping habits in the population looks like the first graph. A small proportion of people stay at home and order online, a similar proportion thinks this coronavirus thing is hoax and shops every day, and the rest of us are somewhere in the middle, shopping one or two days a week.

The problem with sampling shoppers is that people who shop a lot are more likely to be at the store, so the shopping habits of the group we are sampling to test for antibodies looks very different from the shopping habits of the general population. If shopping had nothing to do with the risk of infection, this wouldn’t matter, but the whole point of social distancing is that gathering anywhere puts you at risk, so frequent shoppers are almost certainly at higher risk, probably in direct proportion to the amount they shop. Also, those who shop less are more likely to be reducing their risk in other ways, such as wearing masks and frequent hand washing.

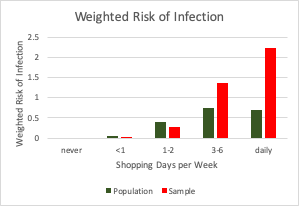

To figure out what all this might mean for the validity of the New York antibody tests, lets make two assumptions. First, assume that your number of potential exposures to the virus is proportional to the number of times you shop. Second, let’s assume the never shoppers are twice as likely to follow infection control guidelines as the daily shoppers and the likelihood of observing guidelines falls in proportion to the number of shopping days. For each category, multiplying the number of shopping days by the risk for each exposure gives an estimate of total risk. If we multiply that risk by the percent of the population in each category, we can get the risk for the population. That is known as a weighted risk. The third graph compares the weighted risk for the population and the sample. You can see that most of the risk is among the heavy shoppers. Since the sample is skewed towards heavy shoppers, it has much higher infection risk, in fact, twice the risk of the general population.

In other words, the actual antibody prevalence could be half of what New York is reporting. That doesn’t even take into account one of the biggest challenges in this kind of sampling, which is that people who are willing to give a blood sample to test for antibodies are not the same as those who rush out of the store and jump in their car. One could imagine that people who want to take the time to be tested might have some reason to be concerned that they have been infected. They were in a crowd. They flew on a plane. They had a mild fever. Their child had a fever. If this occurred, it would also bias the results of the study resulting in an even greater overestimate of antibody prevalence.

None of this takes into account inaccuracies in the test itself, which could bias results in either direction. That is a whole separate issue, but one to keep in mind.

We’ve seen other antibody studies with problems in their design which also concluded there were more infections than previously thought. What do all these antibody tests mean? The short answer is, we don’t know. They suggest that there are more infections than we thought, which would imply that the virus is more contagious (bad) and the disease is less severe (good) than we thought. Because of the problems in the study design, we don’t really know what they are telling us. I criticized the antibody study in LA because they only provided a sketchy outline of their methods in a press release. New York took it a step further by eliminating the press release (apologies to LA). That will take more studies and more careful analysis of the data. I understand there is substantial pressure to release these data, but, unfortunately, the rush to do so has produced more confusion than understanding. At this critical moment, confusion is the enemy.