Recent antibody tests have given new life to the argument that this disease is “no worse than the flu”, so we should stop worrying and get back to work. This argument is wrong in so many ways. Those seroprevalence studies in California and New York have suggested that more than 90% of SARS-CoV-2 infections are asymptomatic. As I have noted, those studies are deeply flawed and almost certainly overestimate the number of asymptomatic cases, but there are definitely infections that occur without the cough and fever considered hallmarks of the disease. So what do those asymptomatic cases mean? First, they mean the disease is more contagious than we originally thought, meaning the risk lies in how easily it spreads as much as in how much risk it poses if you get it. Second, this disease didn’t even exist six months ago, so it is absurd to think we understand all of the ways it can harm us. Death is not the only bad outcome. Before we rush to reopen, we must consider the possibility that, in this case, what doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.

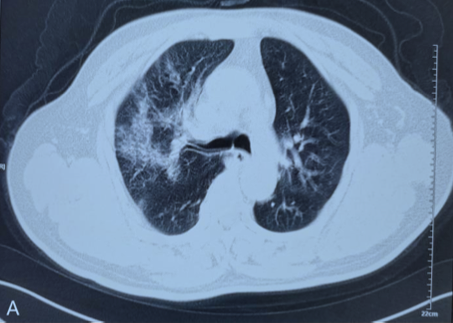

One study of asymptomatic patients found signs of lung injury in CT scans that were similar to those found in the lungs of severely ill patients. Recovery from the scarring caused by Covid-19 for patients who have been on respirators is expected to take a year or longer. It is not inconceivable that asymptomatic lung infections could also cause long term lung damage. If you are young and healthy, you might not notice a 20% decline in lung function. Nothing in the available research can guarantee that you have not injured yourself in ways that we don’t fully understand for a duration that we can’t predict.

The most obvious and deadly symptoms of COVID-19 relate to the severe pneumonia it can cause, but in the course of the pandemic, we have learned that it is not simply a respiratory disease. Research shows that, in addition to the lungs, it can damage organ systems throughout the body, including the heart, liver, kidney, brain, blood, and skin. Until recently, the only way to get tested for SARS-CoV-2, at least here in Seattle, was to have a cough and a fever. We should not be surprised when researchers then report that the most common symptoms in COVID-19 cases are, you guessed it, a cough and a fever. Slowly, studies have recognized other conditions. The measurement of a group of proteins associated with injuries to the heart have become standard practice in managing COVID-19 patients. Sometimes, blood clots are the first evidence of the disease, even in young patients. The gut is routinely infected in COVID-19 and tends to be infected longer than the respiratory tract.

What if these injuries are present in asymptomatic disease? No one notices a 20% decline in the function of their kidney or liver, for example. There are no symptoms. We can survive with only one kidney and half a liver. But having no symptoms doesn’t mean having no problem. It is at least conceivable that people could have asymptomatic disease, but still experience long-term health effects that might not be obvious for years. A virus causing long term health effects is not at all unheard of. Polio, HIV, HPV, and herpes simplex are just a few of the viruses with major long-term consequences. That doesn’t mean SARS-CoV-2 is one of those infections, but we are a long way from being able to say with certainty that it’s not.

Some have suggested that we should simple allow for young people to slowly become infected so that we can develop herd immunity. Indeed, the entire country of Sweden has invested their future in that strategy. We’ll see how that plays out. My concern is that we don’t know what asymptomatic disease means. I have seen the suggestion that the damage done by COVID-19 is something similar to the aging process. Suppose that is true. For the sake of argument, suppose it ages its victims by ten years. If you are 18 and it makes you feel 28, you don’t even notice. If you are 78 and it makes you feel 88, you might just die.

This disease is complicated. Despite the astonishing pace of research, we will spend years trying to understand this disease. In the meanwhile, we should be cautious about dismissing any infection as entirely benign.