The term herd immunity is tossed around as the ultimate endgame for the pandemic, the magic moment that allows us to go back to normal. Unfortunately, as I’ve pointed out before, this is overly simplistic. In particular, the idea that we can get to herd immunity by allowing the young and less vulnerable to become infected leads to a dangerously flawed strategy. The results could be millions dead, hundreds of thousands chronically ill and a vulnerable population (the elderly and those with underlying health conditions) at risk of explosive outbreaks or forced into perpetual isolation.

Defining Herd Immunity

Getting to herd immunity is inevitable. How we get there makes all the difference. On one extreme, we modify behavior to eliminate spread and wait for a vaccine, keeping infections to a minimum. On the other end of the spectrum, we let the disease take its course until enough people have been exposed to reach herd immunity. In essence, we vaccinate with the virus based on the belief that, for most, an infection is of little consequence. Those who have dismissed the severity of this disease since the outset and now rail against masks, limitations on gatherings, and school closings are effectively advocating this second option. With that in mind, let’s see how that strategy might play out.

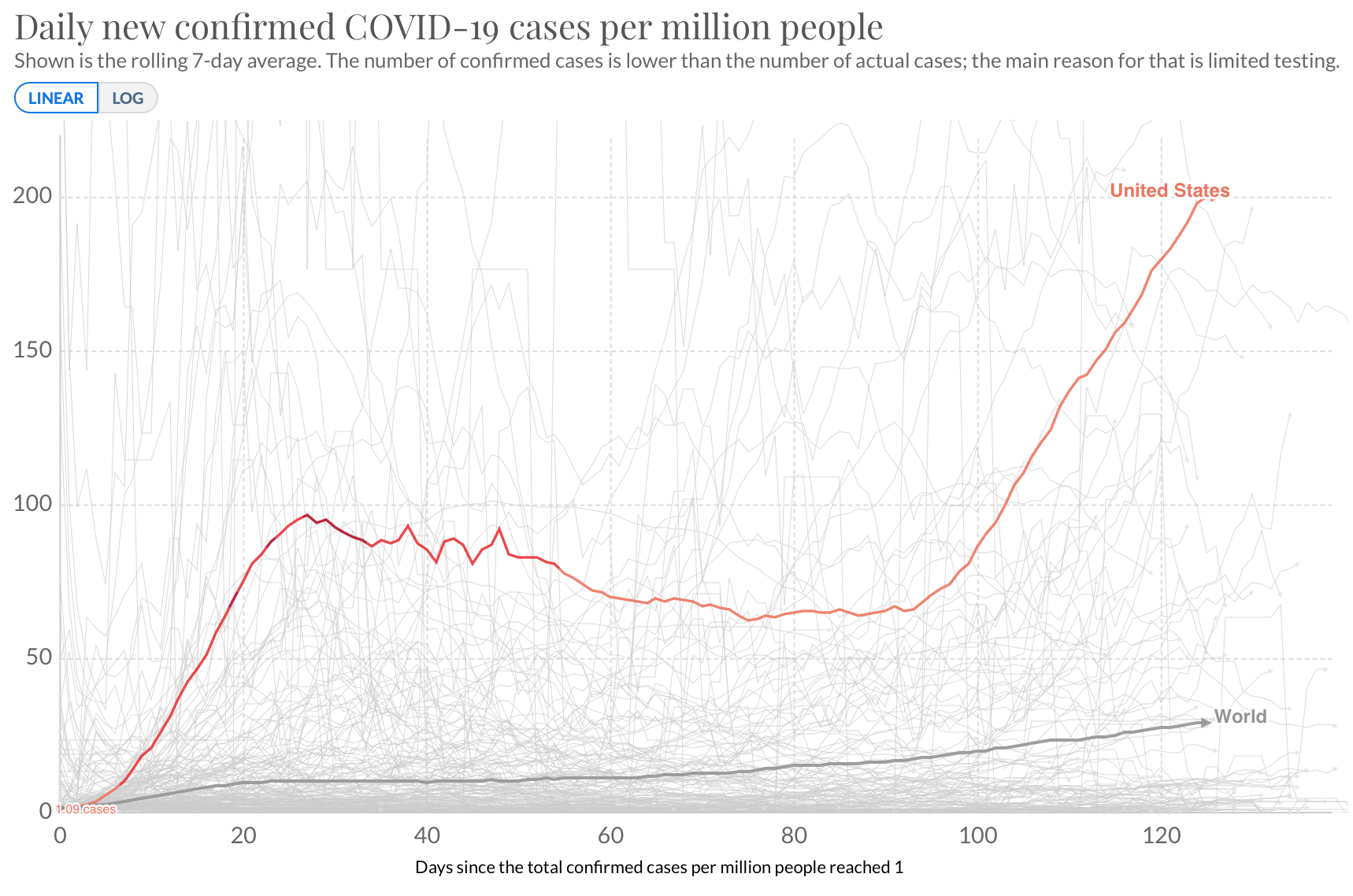

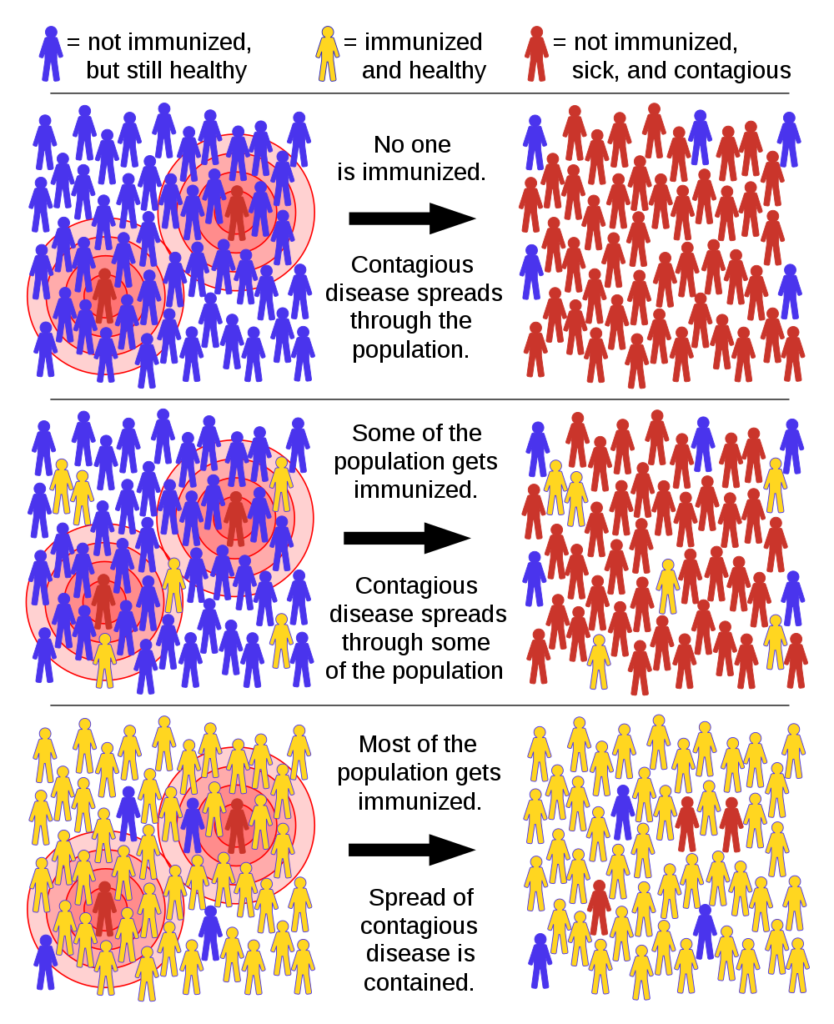

The spread of a disease can be controlled when the average number of people infected by each new case (the Reproduction Number, R) is less than one. R reflects four things: the nature of the virus, the setting (e.g. population density or temperature), the behavior of the population, and the level of immunity in the population. We can’t change the virus or the setting, so the only hope for controlling it lies in behavior or immunity. Epidemiologists delineate the reproduction number when a disease first appears (before there is any immunity or change in behavior) as R0, a measure of the potential for a disease to cause an epidemic. Herd immunity will happen when enough people are immune to hold R below 1.0 with little or no change in public behavior. The portion of the population that must be immune to achieve herd immunity is determined by R0.[1]

Herd Immunity by Infection

Estimates of R0 for SARS-CoV-2 have ranged from 2.0 to as high as 5 or more. Some have even suggested it may be greater than 10. An R0 between 2.0 and 5.0 would correspond to herd immunity levels 50% and 80%, respectively. In other words, 50-80% of the population will need to have been infected (assuming infection confers immunity) to reach herd immunity. This level of infection would have devastating consequences.

Based on calculations described in my most recent post, even the more optimistic case of 50% infection rate for herd immunity, applied to the US population of 328 million would result in 34 million hospitalizations, 8 million ICU admissions, and 1.6 million deaths. Long term health effects, including symptoms such as fatigue, chest pain, difficulty breathing, and joint pain, would affect almost 30 million people. Since they are not the top end of the range, those are optimistic numbers.

In other words, a full throttle approach to opening the economy might cost over two million lives and leave more than 30 million people dealing with long term, possibly chronic health effects. Are Americans really willing to pay that price?

What About Herd Immunity for the Least Vulnerable?

| 50% Infected | 80% Infected | |

| Hospitalizations | 34,440,000 | 55,104,000 |

| ICU admissions | 8,200,000 | 13,120,000 |

| Deaths | 1,640,000 | 2,624,000 |

| Long-term health effects | 28,536,000 | 45,657,600 |

Some have suggested we follow something more akin to the Swedish strategy, which minimizes interventions and maximizes protection of the vulnerable (although the Swedish strategy has been heavily criticized for not taking the protection of its elderly seriously enough, at least initially). This strategy relies on the belief that infections in younger age groups tend to be far less severe, so we can achieve herd immunity by allowing them to be infected. There are two major problems with this approach.

First, our knowledge of this disease, particularly with regard to its long-term effects is limited and we may be underestimating the impact of infecting these younger age groups. The starkest example of this is the relatively recent discovery that COVID-19 can cause a severe, potentially fatal condition known as Kawasaki syndrome, in which one’s immune system runs amok, causing inflammation throughout the body.

Second and, perhaps, more importantly, the notion of herd immunity is based on the idea that a certain percentage of the people encountered by a newly infected case will be immune. Immunity must be evenly distributed in the population for it to be effective. If the 80% of the population that is immune is under the age of 50, that will be of little help if the disease is unleashed on an elderly community. It may help slow the spread if the fraternity brothers become infected, but there are very few deltas psi’s hanging out in nursing homes. And they would never be able to visit grandma or grandpa again.

Defining Vulnerable

In fact, the vulnerable population goes well beyond the 15% of the population over the age of 65. The numbers in the table below suggest that about half of the US population has an underlying condition such as diabetes, obesity, or high blood pressure that puts them at elevated risk.

| Percent of Population | Number | |

| Obesity | 42% | 138,000,000 |

| High Blood Pressure | 31% | 103,000,000 |

| Diabetes | 9% | 30,300,000* |

| Over 65 | 15% | 49,200,000 |

- 80,000,000 prediabetics may also be at increased risk

So, infecting the young may help us get back to work sooner, but it could leave the vulnerable locked away and may have unexpected effects on the young.

Our experience with lockdowns has demonstrated that behavioral changes can control outbreaks of COVID-19. Focused research can help to define the least intrusive set of social interventions required to keep the disease in check. Those changes need to be employed universally (perhaps with adjustments for local factors such as population density and antibody seroprevalence), while we do the hardest thing of all. Wait. The path to improved treatments and, ultimately, vaccines, will require patience, but, in the face of a pandemic, patience is our greatest virtue.

[1] If P is the proportion of people who must be immune to achieve herd immunity, P=1-1/R0.